The

Bath-Gymnasium Complex and the Marble Court

|

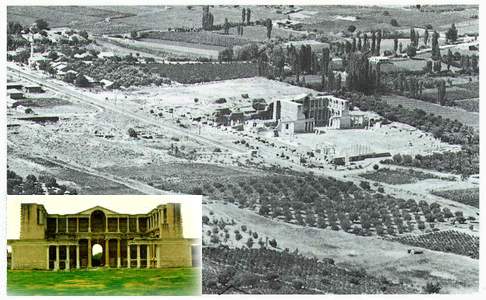

The impressive ruins of the

bath-gymnasium complex in Sardis are easily visible immediarel north of the Izmir-Ankara

highway, some 150-200 meters from the yol-kahve bus stop. With a total area of

nearly 51/2 acres, the complex is undoubtedly the most prominent public structure

of Sardis, occupying a central position in the busy downtown area of the Roman city. The

entire southern frontage of the building is taken up by a row of shops and opens onto a

wide, colonnaded Marble Avenue.

The planning of the complex conforms to the "Imperial type

composed of a series of rooms and halls arranged symmetrically around a major axis and

terminating in a single, large caldarium. |

It displays the

characteristic features of the Roman baths in Asia Minor in which the Hellenistic

gymnasium with its colonnaded palaestra and the Roman bath with its vaulted halls

converged to produce a new type with elements common to both. In inscriptions, these

buildings are referred to as gymnasia or as baths (balnea) quite interchangably.

The closest parallel to the planning of the Sardis complex is the Vedius bath-gymnasium in

Ephesus; other comparable bath-gymnasia can be seen in Miletus, Aphrodisias and

Hierapolis.

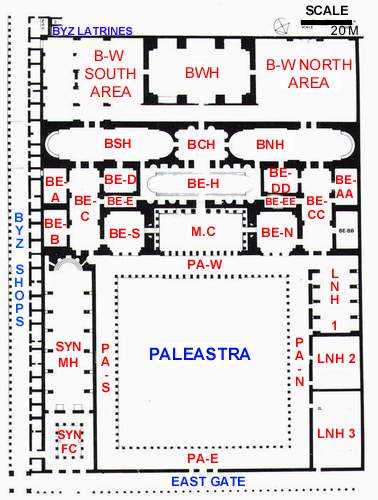

The eastern half of the bath-gymnasium in Sardis is occupied by

a square courtyard, the palaestra, for exerciser the vaulted halls of the western half are

intended for bathing. The halls south of the palaestra were given over to the Jewish

community of the city during the late 3rd century A.D. and became a monumental synagogue.

The main entrance to the complex is from the east side of the palaestra, through a triple

gate, on the main east-west axis of the building; at the west end is Marble Court, a

rectangular space displaying a sumptuous arrangement of columnar aediculae in two stories

and dedicated to the Imperial Cult. On the entablature of the first story is a dedicatory

inscription (in red) mentioning the names of Emperors Caracalla and Geta (his name is

erased) and their mother Julia Domna, A.D. 211. On the podium, a 5th century Byzantine

inscription in verse and prose (in yellow) expresses admiration for the renewed decoration

of the building donated by a civic leader.

Since

exercise and games usually preceded hot bathing, the visitors entered into the complex by

way of the palaestra. After undressing (probably in BE-A, BE-AA, BE-B, BE-BB) and

participating in a light form of exercise, they hurried inside upon the ringing of the

tintinnabulum, which announced the opening of the hot baths. Two identical paths through

BE-N and BE-S into the group of rooms north and south of the Marble Court brought them to

the great apsidal halls BNH and BSH (the base of a Statue of Lucius Verus, ca. A.D. 161,

displayed on the apse podium), probably intended as a grand concourse of social and

ceremonial character. Next, the bathers moved into the heated western section (largely

unexcavated); passing through a series of rooms increasing in temperature from tepid to

warm, they arrived in the caldarium (BWH), which is the main bathing hail with heated

pools. From the caldarium, the bathers moved back into the eastern section into the

central hall, BCH (domed?) and finally into the large oblong hall BE-H identified as the

cold bathing hall, the frigidarium, because of the huge swimming pool occupying the floor

and private basins and pools inside the niches of the walls. After the cold bath and swim,

a final massage complete with anointment and perfume was enjoyed by many as a rejuvenating

termination of the bathing procedure; Sardians were now ready to leave the baths and hurry

to dinner.

The Marble Court (Imperial Hall-Kaise caal) deserves

emphasis not only because of the unusual visual wealth of its rntilti-storied facades, but

also the symbolic meaning of this architecture. Similar space in Roman baths and gymnasia

in Asia Minor have been associated with the observance of the Imperial cult. |

|

The rich and varied columnar

arrangement, the imposing pedimented group of the center, the continuous podia for the

display of statuary and the polychromatic effects of marble may all allude to kingly and

palatial subjects. The setting is also closely related to the stage decoration (scaenaefrons)

of the Roman theater and suggests a link with Dionysus and the Dionysiac nature of the

emperors. The prominence of the Dionysiac theme in the decorative program of the Marble

Court-particularly in the capitals of the screen colonnade-may not have been accidental.

The Marble Court was reconstructed (1964-1973) largely to

its original A.D. 211 stage although some of the features of the later alterations were

retained. During some of these, the north and south apses of the Court were closed off by

a wall (but later cut open with doors) and the central, west apse (for the cult image?)

framed by the gigantic spirally-fluted columns, converted into a passage leading into the

frigidarium; this may have happened sometime in the 4th century when the Imperial cult was

banned or suppressed.

The reconstruction incorporates some 60-65% of the original

architectural ornament. Originally, the rubble and brick walls against which the columns

stand, were entirely covered in marble veneer. The aediculae, as seen today, are supported

by a modern reinforced concrete frame. embedded into the thickness of the massive rubble

walls; the columns carry no loads except their own weight. |

The

Necropolis

The main burial ground

for ancient Sardis was located in the hills and cliffs on both sides of the Pactolus

stream. Several types of tombs have been found in this region. These range in

architectural sophistication from simple, stone-lined cists dug into the ground to

well-built limestone chambers covered by mounds of earth, or tumuli.

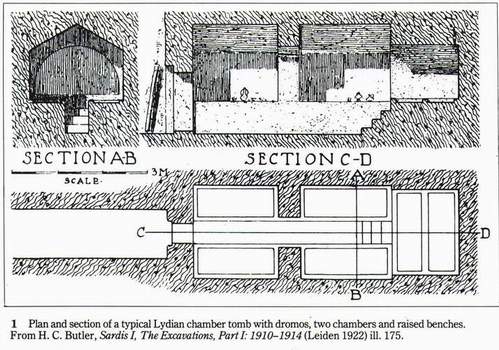

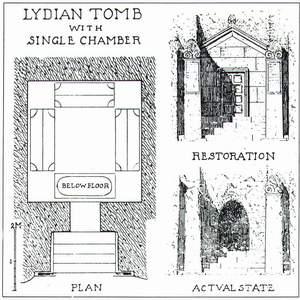

| Of exceptional design is

the stepped "Pyramid Tomb located in the northwest foothills of the Acropolis. The

most common type of tomb is the chamber tomb carved into the hills' easily-worked, sandy

conglomerate. The typical Lydian chamber tomb had an entrance flanked by one or two stone

markers (stelaz), a short corridor (dromos), and one or two chambers,

usually with raised benches against the walls. The earliest of these tombs that can be

dated were made in the 6th century B.C. The necropolis continued to be used through

Persian, Hellenistic and Roman times.Before the Roman period, inhumation was the usual

practice. Bodies were placed directly into cists or in sarcophagi of clay or stone which

were then buried. |

|

In

the chamber tombs, bodies were sometimes laid out on the benches, sometimes placed in

sarcophagi set either on the benches or into the chamber, floors. In tumulus chambers,

bodies were often laid out on stone benches. Funeral offerings included pottery and metal

vases and utensils associated with eating, drinking and personal adornment, lamps,

figurines and jewelry.

|

More

than 1,000 chamber tombs were excavated between 1910 and 1914 by the American Society for

the Excavation of Sardis, directed by Howard Crosby Butler of Princeton University. Most

of these had been plundered in the remote or recent past. Erosion has obliterated many of

these tombs, but the visitor can still appreciate their distribution and concentration.

Directly opposite the Artemis Temple to the west, for example, the broad sloping face of a

low ridge shows many shallow depressions, all of which are tomb cavities. A readily

accessible group of five chamber tombs can be visited by following the modern road along

the west bank of the Pactolus stream to a point approximately 3 km. south of the Artemis

Temple. Just before you come to a tributary of the Pactolus and a small Turkish cemetery,

you will see the tomb doorways in a low cliff to the right, not far from the road.

Less conspicuous today are the tumuli. A few can be

spotted in the vicinity of the chamber tombs, and many, hidden by trees and shrubs,

lie on the skirt of Mt. Tmolus. These tumuli are relatively small compared to those of the

Lydian "royal cemetery at Bin Tepe, 5 krh. north of Sardis. The latter can be seen

from the Izmir-Ankara highway and make an impressive sight, especially in the early

morning and late afternoon when the mounds are highlighted by the sun and cast deep

shadows. |

|

The photo of

stele from Sardis, now in the Manisa Museum, mv. No. 1. Dated to 520-500 B.C. The

inscription in Lydian identifies the owner of the stele and warns against damage or

defacement:

"This is the stele of Atrastas/ son of Sakardas. And thus whoeven destroys or

by misdeed (damages) I he shall pay. (And him?) and whateven/ possession (he may

have?) thus/ to Artemis of Ephesos I vow |

|